PRINT: What’s going on with the filibuster?

By Carson Swick

April 30, 2021

Newswriting II, University of Connecticut

On Aug. 28, 1957, Strom Thurmond of South Carolina took a long steam bath to deprive his body of fluids before heading to work at the United States Senate.

Upon his arrival, Thurmond’s aides arranged for a bucket to be set up in the cloakroom adjacent to the Senate floor. This was not just another day at the office for Thurmond, who took command of the floor at 8:54 p.m. to rail against a civil rights proposal that would authorize the prosecution of those who interfered with African Americans’ right to vote. When his speech was over at 9:12 p.m. on Aug. 29, Thurmond had spoken for 24 hours and 18 minutes — he paused only to urinate in that cloakroom bucket while keeping one foot on the Senate floor.

In taking these drastic measures, Thurmond was engaging in the practice of filibustering, a controversial Senate tradition that has come under fire today. Guided by the precedent of “unlimited debate,” the filibuster allows a senator to command the floor for as long as he or she wishes to stall a vote on a given legislative measure. Filibusters have also been used to stall confirmation votes on nominees to both federal courts and presidential cabinet positions.

Since the Democratic Party regained de facto control of the Senate in January (Vice President Kamala Harris has the power to break ties in her party’s favor), the calls to reform — and even eliminate — the filibuster have grown significantly louder. Earlier this month, Sen. Tina Smith (D‑Minnesota) claimed the filibuster is “doing damage” to American democracy and is responsible for the public’s perception of the Senate as a “broken” institution.

Smith’s sentiment rings true to students at the University of Connecticut, including Mason Holland, president-elect of the university’s Undergraduate Student Government.

“I think that the filibuster has become antiquated in a nation seeking to address the equity and welfare of its citizens,” Holland said. “When there is an important bill going to the floor, it seriously impedes the ability of the legislature to carry out a vote.”

Others in the UConn community, such as political science professor and congressional scholar Paul Herrnson, have noted that the practice of filibustering has been abused by members of both parties in recent years.

“I think the most important point to make is [that] now we have a lot of filibusters we don’t see,” said Herrnson. “It used to be [that] you had to stand and read ‘Green Eggs and Ham’ or a telephone book … Now, the threat of a filibuster is enough to hold things up. That’s where the big abuse is, I believe.”

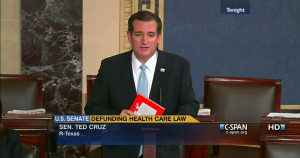

Herrnson’s mention of “Green Eggs and Ham” is a nod to Sen. Ted Cruz (R‑Texas), who in September 2013 delivered a 21-hour filibuster — the fourth longest in American history — to stall a vote on the Continuing Appropriations Act (CAA). The CAA proposed a solution to the fiscal government shutdown of 2013–14, as well as funding increases for the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare.

“I think Ted Cruz’s recent filibuster was … pathetic,” Herrnson said. “He didn’t accomplish anything. It was a waste of time, he offended his colleagues and didn’t have a cause.”

Today, Cruz and other Republicans are staunchly opposed to filibuster reform, as they fear making changes will allow Democrats to steamroll President Joe Biden’s agenda through Congress.

“What would be totally unacceptable would be a unilateral move by one party to significantly weaken the legislative filibuster,” said Sen. Pat Toomey (R‑Pennsylvania), who noted that Republicans never pushed for filibuster reform while holding the Senate majority from 2015 to 2020. The filibuster “has necessitated working across party lines, and the fact that that has been necessary results in more durable legislation. It’s not in anybody’s interest to have laws that bounce back and forth depending on which party is in power … That kind of volatility in our laws is terrible, and we avoid it.”

Despite what the filibuster has become, it was not originally intended to waste valuable time on the Senate floor. In its guidelines for both the Senate and the House of Representatives, the U.S. Constitution established a “previous question motion.”

For the first two decades of the republic, just a simple majority was needed for legislators to cut off debate and bring a measure up for a vote. But this changed during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson.

In an April 6 Brookings Institution Zoom panel on filibuster reform, Sarah Binder, senior fellow in governance studies at the institution, explained that Jefferson’s vice president, Aaron Burr, was the first to suggest that the Senate could abolish its previous question motion.

“It’s 1805, Aaron Burr is giving a farewell speech to the Senate,” Binder said. “He says, ‘You are a great deliberative body, but your rulebook is a little messy … You could drop the previous question motion.’ And in 1806, the Senate codified its rules, and the previous question motion was gone.”

Though several influential 19th-century senators actually favored some limits on debate, the filibuster gradually transformed into the time-consuming measure it is today.

“We can go back [to] the 19th century and find 19th-century leaders trying to get the Senate to impose and create limits on debate,” Binder said. “The great Senate leaders who we recognize and celebrate as great debaters — Henry Clay, Daniel Webster … They all favored limits on debate.”

After the elimination of its previous question motion, it took 111 years for the Senate to address the filibuster. In 1917, it passed Senate Rule XXII, also known as the “cloture rule.” The rule established the number of votes needed to invoke cloture, the process that formally ends a filibuster.

At that time, invoking cloture required a two-thirds (67 senators) vote, but a 1975 amendment to Rule XXII lowered this requirement to three-fifths, or 60 of the 100 presiding senators. Many of today’s reform proposals call for a return to the simple majority (51 senators), similar to the previous question motion outlined by the original Constitution.

Advocates for filibuster reform are quick to point out that the practice has been relatively unsuccessful in preventing legislation from being passed. Of the six longest filibusters in American history, only one — Al D’Amato’s “phonebook filibuster” against President Ronald Reagan’s 1987 defense budget — has blocked the passage of a bill in its final form. However, an amended version of this budget act was ultimately passed.

As such, the aforementioned filibusters of Thurmond and Cruz were both unsuccessful. The civil rights bill that Thurmond stood against ultimately passed the Senate in a 72–18 vote, and it was signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower less than two weeks later. Likewise, the Continuing Appropriations Act passed the Senate in an 81–18 vote and was signed by President Barack Obama less than a month after Cruz’s filibuster.

Progressives have also argued that, since the filibuster has been used by segregationists like Thurmond to stall votes on important civil rights legislation, it is an inherently racist practice.

“I don’t believe that those who first began the filibuster did so with the thought of stifling progress, but it morphed into that very quickly,” Holland said. “It has been used to racist ends, whether I think it is fundamentally racist or not.”

But while scholars generally acknowledge its history of being employed by racist senators, most agree that the filibuster is not a fundamentally racist tool.

“Using a filibuster to prevent … legislation from going forward clearly has racial overtones, but it’s not the tool itself that is racist,” said Herrnson. “The tool is anti-majoritarian.”

Proponents of the filibuster like Toomey have also pointed fingers at Democrats and their progressive allies for their perceived inconsistencies. In 2017, more than 30 Democratic senators signed the Bipartisan Filibuster Preserve Letter, a pledge intended to do exactly as its name suggests. However, Toomey pointed out that only a handful of today’s Democratic senators have maintained this view.

“I’m a little surprised and disappointed, especially with how few of them have publicly come out and condemned the idea [of eliminating the filibuster],” he said.

Though the political pendulum has seemingly swung the other way, any filibuster reform — particularly a reduction to the number of senators required to invoke cloture — is unlikely in the current session of Congress. Sen. Joe Manchin (D‑West Virginia) has publicly opposed all reform efforts, which ensures that a majority of senators will vote against weakening the filibuster for now. Even bringing such a motion up for debate poses a challenge, as Republicans could “filibuster the filibuster” and kill any proposal opposed by party leaders.

“Legislation requires bipartisan consensus, because then there’s no compelling interest in repealing it,” said Toomey. “I think that’s the main reason that we should keep the filibuster and people should care.”

Interviews conducted:

- April 6, Sarah Binder (Brookings Institution) Zoom Panel

- April 8 with Paul Herrnson, via WebEx, paul.herrnson@uconn.edu

- April 13 with Mason Holland, via Instagram, @masonh0lland

- April 15 with Pat Toomey, via telephone, (610) 914‑3800

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.