While the Confederate flag used to be more accepted nationwide, the majority of public opinion has shifted away from the banner. It can still be seen on patches, bumper stickers, and thousands of other places, but public (particularly government-endorsed) displays are becoming rarer.

A July 2020 poll by Quinnipiac University indicates that the flag—and Confederate iconography in general—is falling out of favor across the country. Relevant data is illustrated here:

[infogram id=“confederate-removal-1h0n25y891e7l6p?live”]

The opinions of college students are more heavily anti-Confederate flag.

“It’s a terrible symbol,” said Josh Crow, a 21-year-old political science and economics major at the University of Connecticut. “Sure, at one point it was a banner that stood for an idea. But that idea was ‘people should be allowed to own other people as slaves’. Why you would want to promote that idea is beyond me,” he added.

Crow, who has family in Missouri, acknowledged that people from southern states have a different view of the flag than those with northern predecessors.

“I get that some people had ancestors who died fighting for the Confederacy. And while I can understand the desire to remember them, there are better ways to do that than flying a racist symbol,” Crow said. “People say ‘heritage not hate’, but the heritage of the Confederacy and its banners is a heritage of slavery. That’s a heritage of hate; they’re inseparable.”

UConn history professor Micki McElya agrees that there is a certain nostalgia associated with the idea of the Confederacy.

“There’s a reason that Gone with the Wind is one of the most popular movies of all time,” she said. McElya went on to say that historians have studied the “romantic” impact that the idea of lost causes and rebellions can have.

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (the Lost Cause for short) is school of thought that believes the cause of the Confederate states during the Civil War was for state’s rights and the preservation of American values. The Lost Cause has been described as revisionist, negationist, pseudo-historical and even a cult.

“One of the things we’re seeing move through this history is valorizing the flag, and holding the flag up as a kind of white, rebel identity,” McElya said. “I think rebellion is a really big part of it for a lot of people.”

McElya went on to talk about how the concept of a “victorious defeat” is also a romantic idea that effects how the flag is taken.

“There’s this idea that the south knew they were going to lose,” she said, “but they adhered to their principles so strongly and honorably that they fought anyway. So even in defeat, they won. That story comes to take huge purchase on people’s imaginations.”

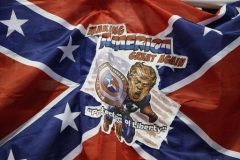

The Confederate flag does get displayed with regularity at rallies across the country, many of which are associated with right-wing politics. The traditional banner has even been melded together with other symbols of conservatism, including the pro-law enforcement “thin blue line” flag, the Gadsden “don’t tread on me” flag and images of Donald Trump.

McElya described how some people and companies in the South have tried to shift the narrative, even describing a clothing company that remade the Confederate flag with Black Liberation colors. “There have been people who attempted to invest it with new meaning… and cleanse it of its historical origins. But as a historian, I just don’t think you can do that,” she said.

NEXT: About the Author »

You must be logged in to post a comment.