By Elijah Polance

UConn Journalism

Reducing combined sewer overflows is a time-consuming and expensive endeavor for the agency that manages Hartford’s sewage treatment. The Metropolitan District Commission settled on a solution not used anywhere else in Connecticut: storing untreated waste inside a giant tunnel.

In 2016, the MDC signed a contract authorizing the creation of this tunnel, called the South Hartford Conveyance and Storage Tunnel. The tunnel will help the MDC comply with the consent order with Connecticut’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, requiring it to correct pollution dating to the mid-1990s. The tunnel was planned to begin holding back waste operate in 2023, but delays have pushed that to 2026.

The tunnel will store excess stormwater and wastewater that ends up in combined sewer systems during heavy rainfall. The precipitation overloads these systems, causing untreated sewage to drain into public waterways and backflow into residents’ homes.

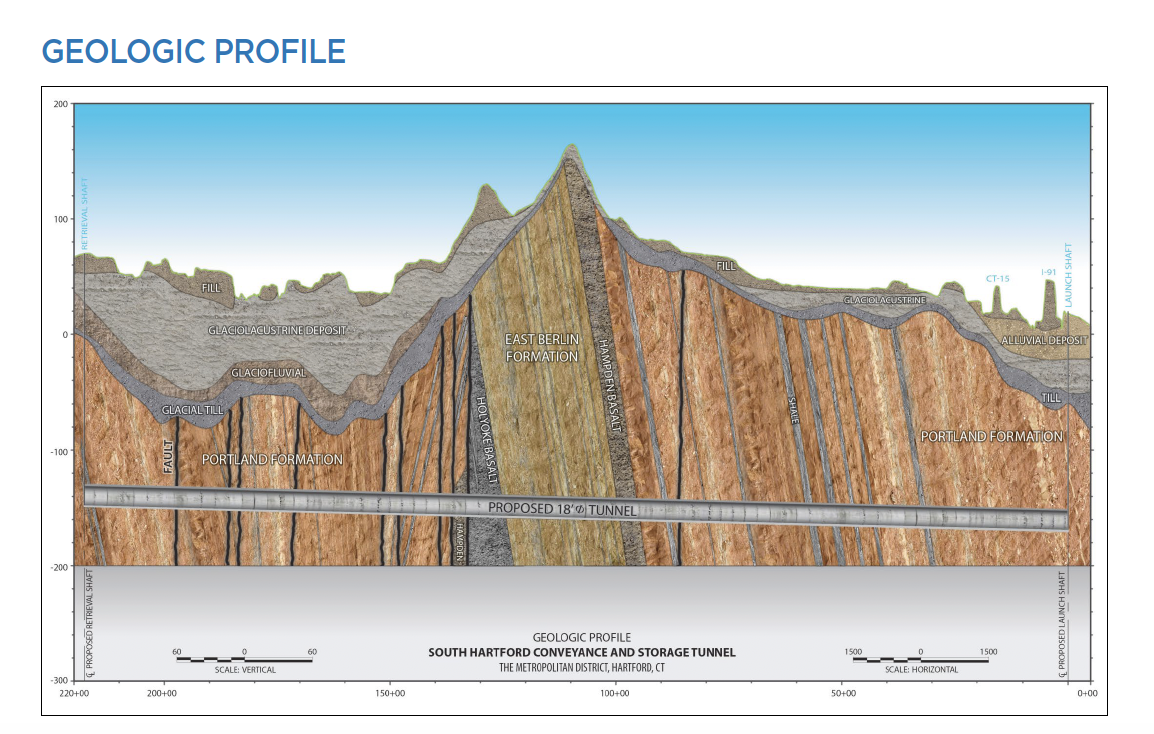

Specifications from the MDC state the tunnel is four miles long and 200 feet below the ground. It has a diameter of 18 feet and can store 41.5 million gallons of water.

“A football field is 360 feet long, 160 feet wide,” said Susan Negrelli, the MDC’s director of engineering and planning. “So picture that with about 100 feet of water on it. That’s 42 million gallons.”

The buried storage tunnel begins in West Hartford, by Talcott Road, and ends in the South Meadows area of Hartford, across Brainard Road from the Hartford Water Pollution Control Facility.

The tunnel will mainly eliminate combined sewer overflows in southern Hartford, especially 10 of the CSOs that overflow into the South Branch of the Park River and seven others that flow into Folly Brook and then into Wethersfield Cove. The tunnel will also take in water from surrounding towns including West Hartford, Newington and Wethersfield, said Nick Salemi, spokesperson for the MDC.

Negrelli said the MDC decided to build the tunnel in southern Hartford because of the consent order requirement to eliminate CSOs to nearby bodies of water, CSO issues in West Hartford, and the proximity to the Hartford WPCF. She called it the “logical starting point.”

“This is where the plant is too, so the tunnel ends at the plant,” Negrelli said. “So anything you’re going to build onto that, you can go further into the system as you may.”

According to Negrelli, the tunnel project involved five construction contracts that included relocating utilities, boring underground to build the main tunnel and shafts, building a station to pump the waste to the sewage treatment plant, and creating conduits for more waste from the east and west.

The drilling for the tunnel began in 2019 and was carried out with a “hard rock tunnel boring machine” built in Germany and known as ISIS. The drilling took three years, finishing in 2022.

The pump station will pump the stored waste to the Hartford WPCF. Because the tunnel runs slightly downhill from West Hartford to this point, gravity will Negrelli said the pump station relies on gravity to get the water moving up 200 feet to get treated.

The conduits are a series of pipes that will allow water to descend 200 feet from sewer systems to the tunnel without letting too much water pressure build.

Salemi said that the tunnel will not become less useful as the MDC separates combined sewer systems throughout Hartford. He said that because the process will take a long time, and because excess rainfall can be an issue regardless of the sewer system, it will remain valuable.

“It’s helpful to deal with the storms, it’s not going to be we build it and then ‘Why did we build this, we don’t need it anymore,’” Salemi said. “It’s part of the system as the way to deal with it.”

Graham Stevens, Chief of the Bureau of Water Protection and Land Reuse at DEEP, believes the tunnel is a valuable short-term solution, but does not solve the root of the problem.

“Tunnels get really complicated, really expensive, and ultimately, although it’s a solution to CSOs, you’re still not getting to the core issue, which is the fact that you’ve got one pipe,” Stevens said.

According to MDC tunnel plans, the need to separate systems was taken into account while planning CSO elimination in Hartford.

In the past, there were proposals for additional tunnel projects to help northern Hartford. But the MDC opted for separation instead, because a tunnel would be logistically challenging because of the distance to the Hartford WPCF, would not refurnish the outdated sewer systems that still need replacing and could end up costing more.

TOP IMAGE: This illustration from the Metropolitan District Commission’s planning brochure shows the route of the waste tunnel underneath bedrock, heading slightly downhill for 4 miles from West Hartford to near the sewage treatment plant in the South Meadows area of Hartford.