By Justin Doughty and Sofia Acosta

UConn Journalism

Since 1994, the MDC has been legally bound to eliminate discharging untreated sewage into rivers through a series of consent orders with the state. The latest of the consent orders, signed January 15, 2025, adjusts deadlines for previously contracted projects and adds some new projects.

This order replaced the modified order from 2023, which had updated one from 2022.

The overseeing agency is the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, which is charged with enforcing the federal Clean Water Act. The consent orders have been modified several times to deal with delays. Sometimes, as the new modified order lays out, projects deemed too large have been broken down into multiple, smaller projects, all with adjusted timelines.

In the new agreement, the MDC was given 19 more months, until July 2026, to complete the sewer separation projects in the Westland Street and Windsor Street areas. Overflows in that area drain into the North branch of the Park River. Previously the deadline for separating those pipes was December 2024.

New projects outlined in the order include sewer separation for “up to 160” private properties in the North End. The MDC will fix outdated piping on private property, saving each homeowner up to $15,000.

This was a major change from previous plans, according to Nick Salemi, the spokesman for the MDC.

“What we did, what was not allowed in previous years—which was the big change—was to be able to do the private property improvements to people’s homes,” Salemi said in an interview. He said “a lot of what we do” is covered by grants through Connecticut’s Clean Water Fund, administered by DEEP. The fund gives grants and loans to cities and towns for work to improve wastewater treatement.

In addition to private property rehabilitation, the modified consent order sped up a number of sewer separation projects, including those on Woodstock and Branford Streets and another project on Tower Avenue. Over $10 million worth of infrastructure improvements have been completed so far on these projects, the MDC announced in spring 2025.

“We actually got a lot of the work done ahead of time and expedited it,” Salemi said.

Other projects slated to be finished in the coming years are unchanged from previous consent orders. These include sewer separation in the Blue Hills neighborhood of the North End and in the town of Bloomfield, which is part of the MDC system. These are expected to be done between 2030 and 2040.

Changing out piping located beneath layers of concrete or asphalt is expensive, time consuming, and disruptive to those that live in the area.

“We’re going to be on your street, cutting out the road, blocking you from going to get your kids. You have to park off site. You have to walk to your car,” said Graham Stevens, chief of the Bureau of Water Protection and Land Reuse at the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, in an interview at the DEEP headquarters in Hartford.

The price tag for these projects is great because of the amount of time and labor needed to complete them. Salemi said many people complain that they can’t see the improvements, most of them being underground or out of sight at the treatment plant in the South Meadows area. “It’s there, but it’s out of sight, out of mind,” he said.

For many people, the long timeframes are difficult to grasp. Stevens said the state is responsible for updating the public on the progress of these projects. Some local residents may not have been born when the original consent order was signed. He said state officials must “reach out to the community and explain what’s coming” to those who may not have even lived in the city when the plan was made.

Nisha Patel, the director of the Water Planning and Management Division at DEEP, noted that sewer separation is a huge undertaking that takes generations to complete.

“CSOs are such a complex and such a big problem that elimination takes decades,” she said “even when you’re being really progressive and really prioritizing their removal.”

As the consent orders over the years have documented, deadlines change to match the realities of these long projects. Thus far, the MDC appears to be on track with the latest deadlines. Only time will tell if the MDC is able to uphold its agreement outlined in the consent order.

The Cost

The total cost of the project to separate sewage from stormwater pipes and to store waste totals $170 million, and the last of the work is projected to be finished around 2040.

In the complex and hilly city of Hartford it takes careful planning and solid funding to undergo upgrade reconstruction projects. Although the MDC has been working with the EPA and DEEP to address CSOs since the 1990s, various factors come into play when it comes to the timeline of seeing results.

Starting any disruptive projects in cities, such as road construction repairs, public transit upgrades, the making of parks and buildings, and utility upgrades like water and sewage line replacements take careful and thoughtful planning.

Director of the Water and Management Division for DEEP Nisha Patel puts these technical and practical complications into context for any big city, but specifically Hartford.

“Say I can’t dig up at Elm Street and disrupt the day-to-day lives of everyone to ultimately separate those lines, or you don’t have enough money for it,” she said. “There’s some other technical challenge, like the ground won’t support two separate pipes.”

She suggested that such challenges require brainstorming for other ways to solve the problem.

There is no question that MDC is responsible for eliminating CSOs, but the agency has said it is not a flood control agency. Yet two state laws passed in 2023 and 2024 require the state and the MDC to work together to stop flooding and to help residents who have suffered from floods.

Nearly $9 million in grant funds were distributed to residents for sewer backup preventers that would keep their basements from flooding with untreated waste. The Blue Hills Civic Association was given $75,000 to administer the grant program.

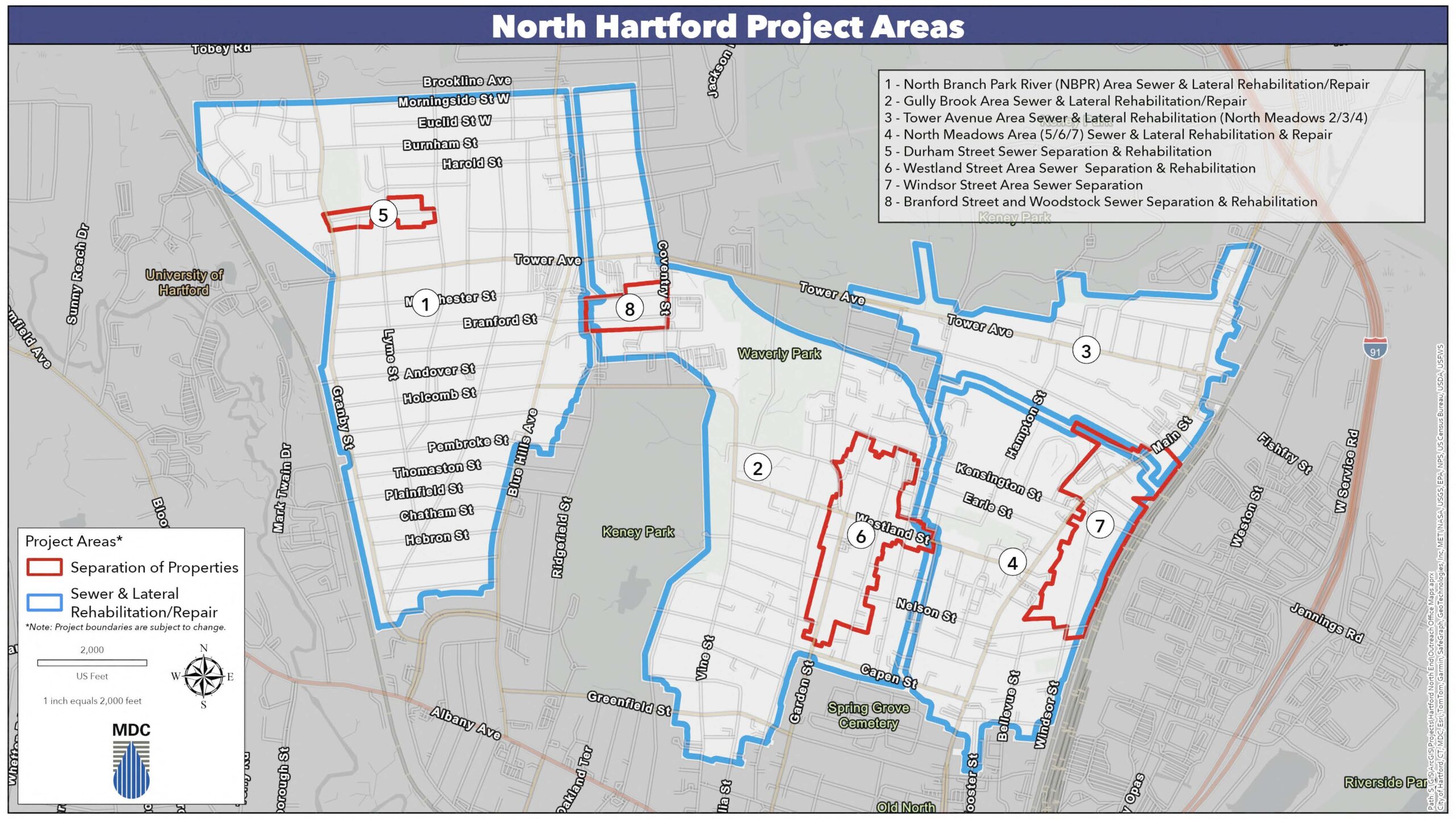

TOP IMAGE: This map shows sewerage system repairs planned in Hartford’s North End neighborhoods. Areas within red borders are where the Metropolitan District Commission is separating storm pipes from sewer pipes, and areas within blue lines where it is lining and repairing pipes. Map courtesy of MDC