Everglades threatened by flooding, erratic weather and intruders

By Purbita Saha

The marl ridge of Cape Sable was once a sweet spot for farmers. Its rich, damp soils made it a hub of agricultural activity, while its prominent coastal location made it ideal for fishing. Yet since the early 1900s high tides have washed over the ridge, nutrients have been washed away, mangrove forests have replaced marshes and the ridge has become barren.

Scientists use the degradation of Cape Sable (A) as an example for what may occur in South Florida after a century’s worth of sea-level rise — Google Maps

Experts say that climate change will cause Florida Bay to migrate north — Photo by Caitie Parmelee

Climate change may soon make similar alterations to other parts of South Florida. Within a century the lower half of the peninsula could resemble a Sea World exhibit. Scientists say that some of the changes, such as flooding and the arrival of invasive species, are somewhat predictable. But others, such as colder temperatures and less rainfall, are more surprising.

“Change in many ways is unstoppable. But what degree of change are we comfortable with?” asked Larry Perez, a science communications interpreter at Everglades National Park.

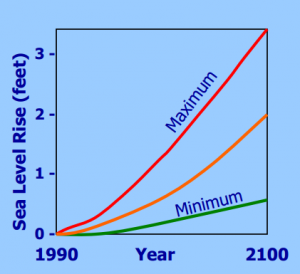

Harold Wanless, a geology professor at the University of Miami, has used current studies and past scenarios to conclude that the Everglades is well on its way to turning into a marine cesspool. Wanless expects there to be a three-foot increase in sea levels within the next century. Such a drastic change, he said, will overtake coastlines, barrier islands, reefs, bays, estuaries and wetlands. “What’s gonna happen in South Florida is we’re gonna keep the water levels high, and then we’re gonna have flooding. Then we’re gonna have a fight,” said Wanless.

This graph illustrates the impact of global warming on the planet’s oceans over the next 100 years — Graphic by Harold Wanless

The mangrove forests that border Everglades National Park are important habitats for aquatic organisms like manatees, shrimp, barracudas, snappers and roseate spoonbills. At the same time, they serve as channels for marine water to mingle with fresh water reserves. With these open avenues, ocean water can drift through the swamp and up to Lake Okeechobee, converting it into an estuary system. Brent Bachelder, a plant biologist from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, said that most of the dominant vegetation in the lake will not be able to survive the intruding salt water.

Harold Wanless is also a chairman for the Miami-Dade Climate Change Advisory Task Force — Photo courtesy of Harold Wanless

Wanless agrees. “The southern Everglades is going to turn into a big muddy, decaying mess,” he said. The situation will be reminiscent of 1935, when a hurricane on Labor Day caused 8 inches of water to drown out the swamp. At the time, many of the mangroves were either knocked down by the storm or destroyed by the saline eruption.

Mangrove restoration should be one of the National Park Service’s top priorities, said Wanless. The forests provide a natural barricade for the park. Plus, they act as a sink by pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and curtailing the effects of global warming.

Another one of Wanless’s suggestions is to use cattails to build up the wetland substrate. This may not be a popular notion, considering that cattails are outgrowing the Everglades’ signature sawgrass. But Wanless said that the invasive plant, which thrives in phosphorus-rich soils, can maximize the organic matter of the swamp and cause peat to form. Unlike the 18,000 feet of porous limestone that make up the Florida peninsula, peat is able to retain fresh water and expel encroaching tides. After the substrate has been stabilized, Wanless said that the cattails would be removed so that the land could be returned to the sawgrass.

Cattails are an invasive species that according to Wanless, can be used to barricade the Everglades so that it does not get flooded out — Photo by Purbita Saha

Climate change can causes heat waves and droughts, but it can also result in cold-weather events. While scientists are reluctant to pin specific weather episodes on climate change, at the beginning of 2011, Okeechobee experienced a record winter with 19 nights below freezing. Bachelder said that as a result of the frost and snow, the population of pond apple trees was wiped out. Since then, the species has not been able to rebound, despite relatively mild temperatures. Pond apple is now considered to be locally extinct in some parts of the Everglades.

Other species, such as live oak and baldcypress, were not affected by last year’s extremely low temperatures. Bachelder said that this may be because they are not limited in distribution like the pond apple is.

Big Cypress ranger Eleanor Hodak fears the preserve may be put in jeopardy if temperatures continue to rise — Photo by Purbita Saha

Precipitation is also a big factor in the climate change equation for South Florida. Eleanor Hodak, a ranger at Big Cypress National Preserve, said that while the entire region depends on water, it is especially critical in the southwest where Big Cypress is located. The cyclical process begins as standing water from the swamp evaporates, condenses into clouds, blows westward and discharges as rain on the terrain.

But scientists at the University of Miami have found evidence that as the oceans get warmer, lower-level clouds are starting to vanish. The leader of the research team, Amy Clement, said in a Time Magazine interview that receding clouds are a good reflection of climate change. In the case of South Florida, they may also be a good reflection of the decreased wet seasons and increased dry spells that will soon tamper with Big Cypress’s lush environment.

Brent Bachelder surveys a plot on Lake Okeechobee for native and invasive floating plants — Photo by Stacy Ann Smith

Warmer weather also makes ecosystems more hospitable to introduced organisms. Bachelder said that in recent years, Okeechobee has seen a boom in invasive populations. “According to the National Weather Service, East-Central Florida just emerged from the seventh warmest winter on record,” he said. This has caused a spike in floating invasives, such as water lettuce and water hyacinths. By densely covering the lake’s surface, the lettuce and the hyacinth are able to overwhelm the aquatic habitat and destroy resident plant, fish and invertebrate populations.

Currently, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has teamed up with wildlife agencies to conduct extensive plant control activities that target these species. But reining in the lettuce and the hyacinth is not easy, Bachelder said. Such efforts require lots of manpower and money.

Larry Perez believes that Floridians should be aware of their precarious situation — Photo by Purbita Saha

Soon, the human population of South Florida will also feel the effects of climate change.

“Miami is perched between a national treasure and an ocean that is rising,” said Perez. Thus, the people of Miami-Dade County end up being the medium between climate change and the Everglades. Protecting both the urban core and the South Florida environment will not be easy.

“We can’t play New Orleans,” said Wanless, “at some point we’re gonna wake up and say, ‘we have to get a hold of this greenhouse gases thing.’ ”